Devottam Sengupta graduated from NLSIU, Bangalore in 2005. He started his career at Trilegal where his work involved practice in Corporate Finance, Banking, Private Equity, etc. After working at Trilegal for almost two years he went for The European Master Programme in Law and Economics (EMLE) on the Erasmus Mundus scholarship. His EMLE degree was conferred jointly by the University of Hamburg and the University of Manchester.

After returning from the EMLE programme he joined Amarchand Mangaldas, Delhi in 2008 and then later in 2011 he moved in-house to Cargill where he tasted Structured Trade Finance. He is now responsible as the Senior Legal Counsel at Louis Dreyfus Company (LDC), Singapore where he continues to work in Structured Trade Finance since the last three years.

In this Interview Devottam shares his insights with Rounak Biswas of SLS, Pune on the topics raised by Reshma Ravipati of NLU, Jodhpur.

How would you like to introduce yourself to our readers?

I am the Global Lead Lawyer for Structured and Trade Finance at the Louis Dreyfus Company Group (LDC), based in Singapore. LDC is one of the four biggest agricultural product traders in the world, and is headquartered in Geneva. Working with the STF business, I get to work on banking and trade transactions across the globe – at the moment, I’m advising on matters in places as disparate as Uruguay, Kenya, Qatar and Vietnam!

However as anyone who has worked in-house would tell you, – you are almost never doing only what your role was meant to be! You have to wear many hats, juggle many roles and be able to pitch in wherever needed to be a successful in-house lawyer. As such, I am also the financing counsel for the LDC Group for Asia-Pacific and a part of the global M&A team.

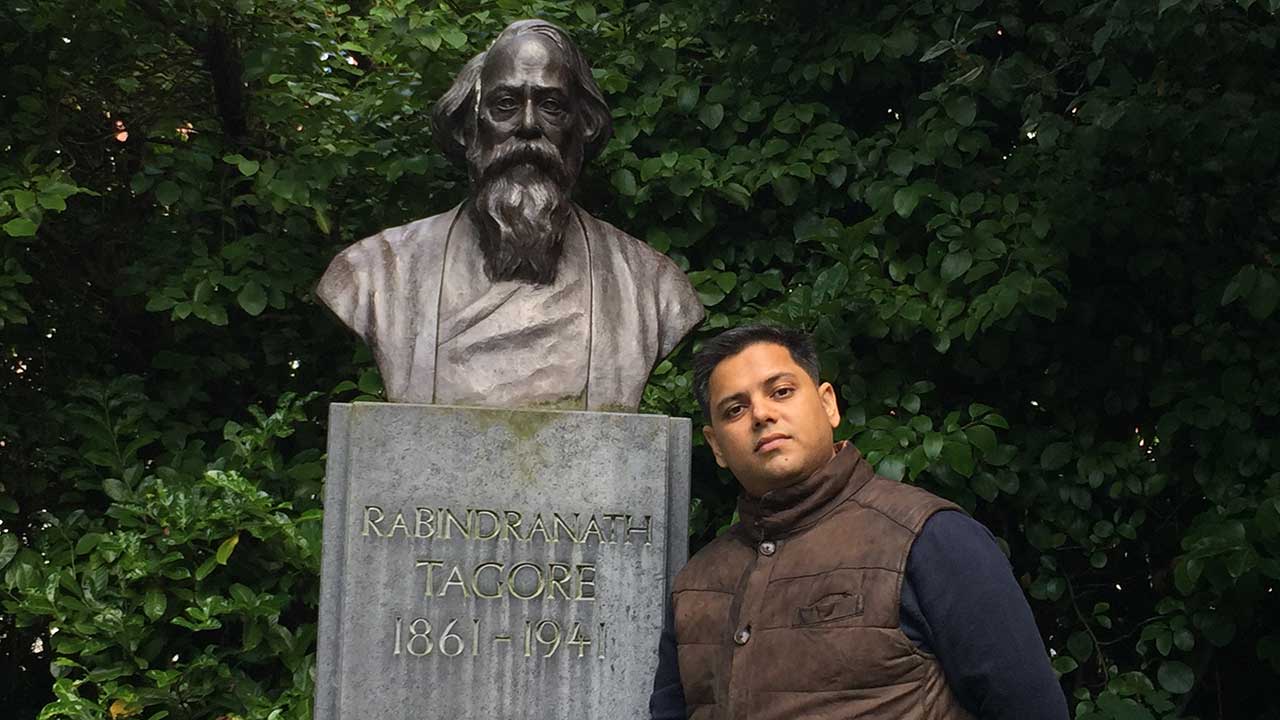

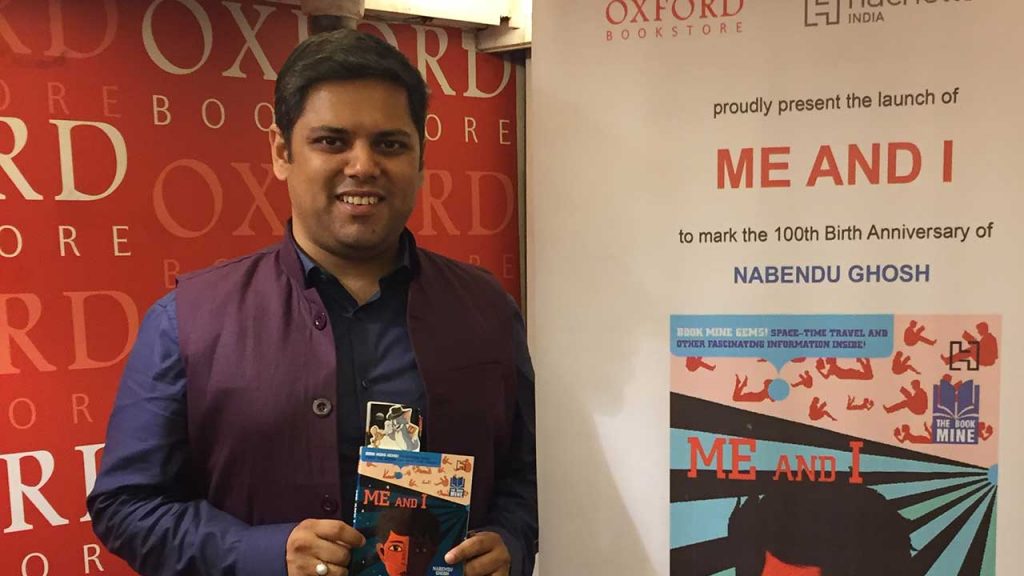

But my work is only a part of my life. I’m an avid traveller, a fanatical foodie, a published translator, budding Instagrammer and a regular pub quizzer. My varied interests help contribute to my ability to view issues through multiple lenses, which in turn helps me in bringing new and fresh energy and insights to my work.

Why did you choose to pursue a degree in law, amidst the many options that you had after school?

Sadly I don’t have a great answer for this question. I got into law more by chance than a focus on the profession. My legal path was built by the simple fact that I cleared the NLSIU entrance, while I had assumed I would end up doing something in business administration. However, my first year at NLS really changed my perception of law – I stopped looking at it as a job but more as a vocation.

I do not think that one becomes a lawyer by the simple fact of graduating from law school. The key advantage of the study of law is that you come away with ingrained core skills which give you a foundation to pursue any profession you choose to pursue thereafter. My wife is a lawyer by training but works with the United Nations on social policy by profession; I have close friends who are running successful businesses; there are those who have succeeded in investment banking or consulting. Your options following law school are only limited by your imagination. And this I learnt in my first year of law school, which made me want to stay on and see it through. The rest, as they say, is history.

Give us a brief overview of your personal experience at NLSIU. Is the NLU culture truly more conducive to legal education, as compared to other universities that provide legal education?

As with all meaningful experiences, my time at NLSIU was full of ups and downs, just as one’s student life should be. Alongside my law studies, I was deeply involved in co-curricular and extra-curricular activities. During my time at NLSIU (2000-2005), I participated in pretty much every extra-curricular activity, organised some significant academic conferences, was on the student committees, helped my classmates get jobs, and represented NLSIU at various competitions. All of these were as essential a part of my education as my classroom studies, but I wouldn’t have minded a higher CGPA! I can however definitely say that pursuing these multiple co-curricular paths helped me become a more well-rounded individual and have helped me build my career post NLS.

I think the question on NLU culture is a little misleading in today’s world. I think very little distinguishes NLUs (as originally envisaged) from private law schools and the traditional law schools. The question therefore isn’t so much on NLU culture as it is about culture of the best law schools. The best law schools in India, whether you’re talking NLSIU, GLC Mumbai or ILS, all have a culture of learning and imparting professional skills. Besides, what is an NLU today? Amity Law School, Army Institute of Law, ILS and JGLS have the same format, without being “NLUs”, so what is the dividing line?

By professional skills, I don’t solely mean the skills required for litigation or corporate law job, but the most basic ones required for all lawyers – research, analysis, problem solving and drafting. No matter which stream you finally end up in – academia, in-house lawyering, completely non-legal jobs, or politics – these basic skills help you succeed. Therefore, it’s more a question of whether your institution creates the right environment and delivers on imparting these skills.

I think the advantage NLUs start out with is that being (a) residential and (b) over five years, there is more time to deliver and hone these skills, compared to a non-residential or a three-year law school. What the institution (and the students they select) does with the time is what sets apart the best ones from the also-rans. There is no point being structured as an NLU if the students don’t receive access to the best academic resources, to high quality internships, backing for co-curricular and extra-curricular activities, and the space to practice what they learn in the classroom.

One of the key elements of NLSIU’s success, in my mind, is that the student body has practiced what the Constitution of India has preached. Freedom of speech and expression is sacrosanct, there is equality for all, principles of natural justice are followed and there is representative decision making. I think this manifestation of lessons learnt in the classroom and in other facets of campus life helps to concretise certain core beliefs in most students. This, together with the academic rigour needed to write numerous papers and provide analytical answers in most exams does help in building future lawyers, and I’m happy to see so many NLUs have successfully adopted these methods.

What are your areas of specialisation and how did you go about choosing these fields to specialise in?

Formally, I am a structured finance lawyer and a specialist in trade finance, though like I said at the outset, I still consider myself a generalist. Even though I have been a trade finance focused lawyer for many years now, I have concurrently worked on M&A, private equity transactions and general corporate finance, and don’t hesitate to get involved in other areas of law as and when I get the opportunity.

I didn’t choose structured and trade finance so much as it chose me! My first job after NLSIU was with Trilegal Mumbai, which was best known at the time for its banking and finance practice. The years I spent at Trilegal were during the booming mid-2000s, and I was fortunate that I was able to work on some of the best structured finance work to have taken place in India. This experience laid the groundwork for pretty much the rest of my career, with subsequent jobs with Amarchand & Mangaldas Delhi (now Shardul Amarchand), with earlier Cargill and now LDC, all being grounded in the banking and structured finance experience I gained at my first job.

At what stage in one’s law school life must one pick a specialisation? What words of wisdom would you offer to someone who is yet to make this choice?

My humble advice is one should never pick a specialisation voluntarily, especially not in law school. Unless you are absolutely certain you will be miserable doing anything other than criminal law litigation or writing books on public international law, most of us have very little experience of the day-to-day realities of professional life while in law school, and certainly not enough to make career-defining choices before we’re old enough to drink in most states in India.

I would instead recommend gaining as much experience as possible in a wide variety of fields, so that when you graduate, you are able to cope with anything life throws at you. Whether it’s a corporate role, or litigation or studying further, extra knowledge will never be a waste. Lack of knowledge on the other will always hold you back.

The right time, to my mind, to specialise, is two to three years after graduating from law school, where you have a more realistic idea of what you want to do with your life and what you enjoy doing professionally. This is borne out by the international standards in the practice of law – US law schools are postgraduate institutions, which do not accept students straight from their undergraduate degrees; UK firms require all associates to have spent two years on a training contract, where you’re shuffled around to gain as much experience as you can, while the firm judges what you’re best suited for. Anecdotally too, I find that most of my friends have ended up specialising in fields quite different from those they had in mind when in law school.

By all means, we should aim for certain jobs which attract us the most, and do everything that it takes to be considered for that job, including gaining as much knowledge relevant to the dream job as we can, but that shouldn’t to the exclusion of general knowledge.

Who was your mentor, or main source of inspiration who/which motivated you all along the way?

Throughout my career, I’ve been fortunate enough to consistently have had seniors from whom I drew inspiration. Before your readers get the wrong idea about this, I’m not saying this to be diplomatic or politically correct! I firmly do believe that I have learnt something from every senior I’ve worked with, and each of them has in some form or fashion motivated me to do better or helped me to grow as a lawyer and a person. I have even found inspiration from some of my talented and hardworking peers. I must however say that working under Mr. Shardul Shroff was a great learning experience, given the breadth of work he handles and the depth of his knowledge.

A mentor though isn’t necessarily a person who has always been nice and helpful to you, but someone who has taught you lessons you needed to learn in order to grow, even if you do not realise it at the time. You can seek out inspirational figures, but a mentor will not merely inspire you, they will be teachers who can show you the right path. This is not restricted merely to legal skills, but also extending to crucial soft skills of people management as well as ability to understand business concepts and come at issues from a solution-oriented lens.

That said, there are individuals whose advice and training have been foundational and critical to my career. From my private practice career, I owe a debt of gratitude to Avinash Umapathy (now at CAM) and Nishant Parikh (Trilegal) for their patience and guidance, which certainly did help shape my career in unexpected ways. And from my in-house life, Aditya Bhagat (India legal head at Cargill) and the current APAC GC for LDC- Massimiliano Talli have taught me about what it takes to be a successful in-house lawyer and become a successful team leader.

Last but not the least, my understanding of the structured trade finance business would be incomplete without the guidance of Gopul Shah, who used to head the business for Cargill in India.

You had previously worked with Amarchand & Mangaldas, Delhi and Trilegal, Mumbai. What does it take to make the cut and land a Tier-I job?

What does it take to make the cut?

You should be able to demonstrate to the recruiter an ability to work hard, to deliver solutions and an interest in the job beyond the paycheck. Whether this is through selection of elective courses, moot court excellence, articles in journals, organising academic conferences, or something else altogether, there really isn’t a “correct” answer, but it has to be apparent from your CV. It is not sufficient to be considered the smartest person alive by your classmates – what you are able to put down on paper is what helps you get to your dream job.

At the same time, it is not enough to say you are interested in a particular job if you haven’t done the basic research on it and have no idea what it takes to do well in that field. For example, when applying for a corporate law role, the one article you might have written on corporate law on the developing law of insolvency or that internship with a small corporate law firm in your second year might be more valuable than winning a medical law moot or a dozen debating tournaments. While moot court wins and debating experience does undoubtedly have value, the corporate law angle would demonstrate that you know your audience just that little bit better.

What law firms look for?

A disclaimer here – what law firms look for when they’re hiring varies significantly between Indian firms and foreign firms, especially when the economy is booming. In times of rapid growth, the only thing a firm might look for is a heartbeat. That’s a joke, but only just – firms often hire large numbers during good times, secure in the knowledge that they will naturally shed underperformers when times are bad.

But to be more specific, what gets someone hired in a top tier law firm are certain skills needed to succeed in a corporate law firm role, and which is what most partners look for in prospective associates.

Primarily, these skills would be

- ability to get things done,

- ability to multitask and cope with pressure; and

- of course a high standard of core legal skills (research, analysis, problem solving and drafting).

Of these, I think the third one is pretty self-explanatory, so I will focus on the first two parameters.

When I would interview associates, I would rate a person with decent grades but a broader set of skills over someone who might be ranked first in class but have nothing else at all on their resume. A successful corporate lawyer has to be able to do many things at once –juggling 5 transactions at the same time, developing client relationships, working to grow their practice, thinking proactively of their clients’ future needs, chasing up on bills – no corporate lawyer I know succeeds without being able to multitask.

Being able to multitask brings with it the ability to cope with competing demands and pressure. You will never have enough time to do everything that is required of you in a law firm. And I don’t mean in your early associate days, but through your entire career as a corporate lawyer. The demands and pressures change, but if you’re not multitasking and trying to cope with time constraints, then your growth as a corporate lawyer may stall.

And a corollary to the demands on your time is the ability to get things done. This is not the euphemism common in government offices, but refers to being able to find ways to deliver on what you’ve been asked to do. Whether it’s by doing simple things like being enough of a team player for others to help you out when you are overloaded, or your ability to prioritise, or being able to quickly find the right answers, the ability to deliver on promises and expectations goes a very long way in ensuring professional success.

Lastly, it might be useful to do some research as to which teams the firms hiring for, even if it is for more senior roles. Some teams need more people urgently than others, and it’s always best to spend a little bit of time trying to figure out how you can demonstrate your value for existing vacancies than be lumped in for general roles.

What is the level importance given to a student’s Grade Point Average with respect to recruitments at Tier-I firms?

It’s an important consideration as a cut-off. Like I mentioned earlier, law firms try to gauge a candidate’s skills in making a hiring decision, but GPA standalone provides limited insight on quality. What it does provide though is a useful benchmark for determining which students are likeliest to have the necessary skills and qualities.

I personally had an average GPA, so I wish this wasn’t true, but the fact of the matter is that law firms, especially Tier 1 law firms, have to use GPA a screening mechanism. Each firm receives hundreds of applications for internships and entry level associate roles, and there are a limited set of objective criteria for predicting which applicants might be good enough for the firm – reputation of institution, GPA and past work/ internship experience.

And more often than not, you’ll be competing with people from the same law school and with similar work experience. GPA is therefore bound to be a major differentiator at the outset. However, once that first hurdle is cleared, then it comes down to subjective criteria, where the lower GPA candidate might actually be a better fit than the higher GPA candidate.

How do you say interns should go about their work at a firm like Trilegal, so as to get noticed in a positive way in the limited time they have?

Be excited, willing to learn, open minded and proactive. If you’re morose about being at the firm, whatever be the reason, it will show and come across to the associates and partners as disinterest. No associate is going to stick their neck out for an intern who does not seem to be excited at the prospect of being at the firm.

Another quality the lawyers at the firm will pick up on is your willingness to learn. Assume you’re pulled into something you’ve never looked at before, or even heard of – very few law students would have ever come across Food Safety Standards or Air Information Circulars. It’s how you react to such a challenge which will be noticed. Did you come in with a closed mind or a willingness to learn and take on the challenge? Did you give up immediately or did you work past the difficulties in finding an answer? Did you go back empty handed or did you ensure you had some leads, if not an answer? More often than not, the partner or associate asking you the question already knows the answer, but wants to check your response.

Open-mindedness is pretty crucial when interning with any law firm. So you didn’t get the office or the team you really really wanted…so what? You’re still at the firm right? The aim is to get the job offer, so it’s better to be a star intern in the IP team than to be the person who moped about because s/he wasn’t in the Capital Markets pool. Once you get the job, you can always seek an internal transfer after you’ve established your worth. One of the best juniors I’ve had in private practice was originally hired for Amarchand’s tax team, but is now an M&A partner at SAM.

Lastly, proactively seeking out work will take you a long way. Just because you’re not being given work is no reason for you to skip out early or take a day off for a Netflix marathon. As an intern, you should actively go up to associates, if not partners, and ask for work. If you see your seniors struggling on a project, go and offer to help. If your fellow intern is struggling, lend a hand. You may not learn anything or even be given work, but the fact that you asked will be remembered.

One bonus tip – always assume you’re auditioning for the job during every interaction at the firm, whether in office or outside. That means always put forward yourself as a candidate, whether that is when you are having coffee with your senior from law school, at the office party, or if you’re stuck in the elevator with the managing partner.

What was the reason for your transition from firm practice to being an in-house legal counsel for corporate houses? What is difference (if any) in the work culture at the two places?

I moved from private practice to in-house legal as I wanted to move from a service provider role to a business side role and more specifically participate in the practical running of a business. I acknowledge that some lawyers are so trusted by their clients that they become business advisers, but this more an exception than the norm. Especially in India, but also true generally globally, private practice lawyers have little to no say on business decisions. In my mind I had always wanted to get closer to the business side of things. To this end, even my LL.M wasn’t a traditional legal degree, but a Masters in Law and Economics.

This is not to generalise and say that in-house lawyers are all heavily involved on the commercial side, but if you choose your employer wisely, build your business skills and demonstrate your acumen, business teams will get you involved on commercial decision-making. I have been fortunate that both in Cargill and in LDC, I’ve worked with business teams who have valued my skills and judgement enough to make me a part of the business decision-making, rather than look at me only as a legal expert or worse as a legal roadblock.

But I do not want to generalise and compare private practice and in-house roles. There are already too many negative stereotypes and myths about in-house roles, and it will not be helpful to make sweeping statements. Every private practice role comes with its unique challenges, as does every in-house role. So I think it would be better served for me to try and dispel some notions about in-house life.

One of the silliest and most baseless assumptions I hear about in-house counsels is that lawyers go in-house when they want an easy life. This certainly is not true in today’s cost conscious business world. No company will tolerate the cost of an in-house lawyer who is not working at least as hard as the business team; nor will they tolerate an in-house lawyer who incurs additional costs on external counsel. If anything, in recent years, in-house legal teams have expanded greatly in pretty much every company across the board, which is a testament to how cost effective in-house advice is in comparison to external advice.

Given the increasing role of in-house legal teams, a natural corollary is increased pressure to deliver. While private practice lawyers live or die by short deadlines, in-house lawyers face a different type of pressure – you MUST find the right answer for your company, because you will be held accountable for it. You cannot go back with a bad answer, because if things go sour, the external counsel is not the one being held accountable. Whether it’s in finding a solution to a seemingly impossible problem, or finding hidden risks in that otherwise sure deal, external counsels are at best trusted advisers, but not the decision makers. In-house lawyers on the other hand are on the hook for every decision taken by them. Remember – no business means no need for your job. So you better get it right!

Which would you recommend for a fresh graduate who’s looking to start off his/her career?

There isn’t a right answer to this. For fresh graduates, it might be better to join the in-house team of some companies than to join some law firms, where the former could be a role better suited for the person’s career goals. Many friends have started out in in-house roles and are now highly rated partners in law firms. On the flip side, some friends had joined law firms and had very quickly become disillusioned and left the practice of law altogether. It depends very much on the law firm or the company in question. My recommendation to any fresh graduate is to do their research on the job before saying yes or no. Is the law firm known for promoting their younger talent? Do they work on areas that interest you? Do they have a high attrition rate? Do they have a reputation as a good employer? If the answer to these is no, then you might be better off going to a company.

At the same time, there are some critical questions which one should reflect on when considering an in-house role:

What kind of work would be expected of you as a junior lawyer?

If the answer is primarily corporate secretarial and filings, run away at top speed. Conversely, if you’re expected to review contracts and provide memos, you might actually end up with more responsibilities than your roommate who joined a law firm.

How big is the in-house legal team and which business teams will be your internal clients?

Small in-house teams are not necessarily bad, especially if you have a large number of internal clients. But size usually correlates to greater amounts of work for the legal team, which could give you as much exposure as your law firm friend.

At what stage in transactions is the legal team brought in?

The earlier the better for you personally, and more generally, would be demonstrative of higher responsibility.

Who are the internal stakeholders or clients for the role?

If your clients are primarily business teams or Treasury, your role will give you greater transactional approach, than if you’re primarily dealing with other support teams.

Give us a brief overview of your current work profile with Louis Dreyfus Company (LDC) Group. What does a regular working day look like for you?

As the Global Lead lawyer for structured finance at LDC, I am the primary point of contact for the financial services business of the company, and responsible to the business for review of all transaction structures and documents. At the same time, I am responsible to the senior management of the company for controlling risks taken by the business team and for ensuring compliance with company policies and laws generally.

What this means on a day to day basis is that I have to work with my colleagues on the business side to ensure that we proceed with transactions with counterparties in a manner which is in compliance with the law and safeguards the company’s interests while minimising risks. To do this, I review transactions while they are still being planned, review the transaction documents, work with external counsel to ensure we are accounting for all regulatory requirements, participate in negotiating documents with counterparties, and lastly, work on addressing any concerns raised by other stakeholders and the senior management of the company.

Given the broad geographical scope of my work, I am often working simultaneously on transactions from places as dissimilar as Colombia, Nigeria and China! Which also means that I could find my mailbox bombarded overnight by my colleagues in South America, try and resolve crises during the day for the China team, and in the evening, get onto calls with colleagues in Africa to negotiate with a counterparty there! Thankfully I have a great set of colleagues on the business side, and great support from juniors in the legal team.

How important is it to have a foreign qualification in working overseas as an in-house lawyer? Can someone with only an Indian qualification be considered for international roles?

It is not a prerequisite but it definitely helps to be dual qualified. We are fortunate that India has a common law system, which allows us to easily understand and work on transactions under English or other common law systems. But the Indian legal system is still not as commonly used in international trade as those from England, New York, Singapore or even China. It is possible to be considered for international roles within companies in certain very globalised segments – IP related roles and banking come to mind – but without a second qualification, you’ll have a tougher time demonstrating your knowledge and ability.

The good thing is the English law qualification is open to Indians without much hassle, under the Qualified Lawyers Transfer Scheme. It is not cheap, but given the relative cost of an LLM, I think investing in English law qualification is a better bet, especially if it’s one or the other. Even if you never end up working abroad, it shows your international credentials to companies and your interest to international law firms. Also, it might give you an edge when it comes to some very highly sought after in-house positions.

Is there any other suggestion you would like to make to our budding lawyers?

Keep learning and investing in your personal growth. It doesn’t matter if you work in litigation, private practice, in-house or in academia, if you stop learning, you will cease to be relevant as a lawyer.

Also, underestimate the importance of networking in the legal profession at your own peril. It is easy to make fun of people who seem to be endlessly attending conferences, or those posting on professional networks or writing for magazines, but remember that your dream employer could be at that conference or reading your post or article and ultimately can will help build your profile to show why you are the ideal candidate for your dream job.